High atop a narrow plateau on Pittsburgh’s North Side, the neighborhood of Troy Hill has watched over the city’s rivers and industries for nearly two centuries. In the mid-1800s, one might have stood on this hill and heard the sounds of church bells mingling with the din of mills below, or even the squeals of livestock being herded up a steep cobblestone path. From its German Catholic roots to its proud working-class heritage and modern renaissance, Troy Hill’s story is a microcosm of Pittsburgh’s own evolution. This historically German hilltop village – once an isolated hamlet known as New Troy – has transformed over time yet retained a close-knit community spirit. Let’s journey through the vivid history of Troy Hill, complete with bustling breweries, torchlit Saengerfest celebrations, immigrant tales, and enduring landmarks that continue to tell the tale of this unique neighborhood.

Origins on a Hilltop Plateau

Troy Hill’s beginnings trace back to the late 18th century, when the area was a wooded part of the “Reserve Tract” north of the Allegheny River. In 1788, surveyor David Redick mapped this land for future settlements . The hilltop remained largely undeveloped until the 1830s, when entrepreneur Thomas H. Baird and others laid out a village called “New Troy” in 1833 . The name was likely inspired by Troy, New York – local lore even suggests one early landowner hailed from that area . At first, New Troy attracted settlers of English, Scottish, and Irish descent, evidenced by early institutions like an Episcopal cemetery “for persons born in England,” established on the hill in the 1830s . Yet this initial Anglo influence would soon be overtaken by a wave of German-speaking immigrants who found their way up the hill.

Throughout the early 19th century, the plateau overlooking the Allegheny remained sparsely populated farmland. It was Captain George Wallace, a Revolutionary War veteran and prominent landowner, who first acquired large sections of the hill (then part of Reserve Township) in the 1790s . Wallace’s heirs later sold parcels to developers as Pittsburgh’s growth put pressure on surrounding lands. By the 1830s, as Allegheny Town (present-day North Side) grew into a borough, enterprising minds saw the hilltop as the next place to build homes overlooking the burgeoning industries along the river . Thus New Troy was platted, envisioning a hilltop community with commanding views and fresh breezes above the smoky city.

A German-Catholic Village Takes Root

It wasn’t long before German immigrants became the heart and soul of Troy Hill. In the mid-1800s, hundreds of German-speaking families began trekking up the wagon paths to settle on the hill, bringing Old World traditions with them . They were drawn by jobs in the mills, tanneries, breweries, and railroad yards lining the Allegheny River below . Life on Troy Hill offered a refuge from the crowded city – a place where they could build a “Heimat” (homeland) reminiscent of the villages they left behind . By the time of the Civil War (1860s), Troy Hill was predominantly German and devoutly Catholic, though German Lutherans soon followed as well .

One early catalyst for this migration was the establishment of a small Catholic cemetery on Troy Hill in 1842 . The German Catholic parish of St. Philomena in Pittsburgh purchased land on the hill to bury its dead, a decision that quite literally consecrated Troy Hill ground for the immigrant faithful . With a cemetery in place, families had reason to climb the hill, and many chose to live nearby. By 1866, roughly 100 families lived on Troy Hill – enough population to warrant their own church and to cement the hill’s identity as a village. Residents even began referring to the area simply as “Troy Hill,” dropping the “New,” as the community developed its own character.

During these formative years, Troy Hill was still officially part of Reserve Township, outside the city. Neighbors relied on each other, forming a tight-knit enclave bound by language, faith, and shared hardship. In 1868, a young local man, Henry Reinemann, vividly described a German Saengerfest (song festival) taking place on Troy Hill: “The Saengerfest commences here today, and the streets are gaily decorated with evergreens and flags… Tonight torchlight procession and concert…” he wrote to his brother in Germany . One can imagine the scene in the summer of 1868 – German banners fluttering, voices raised in song, and a torchlit parade snaking along the hilltop lanes. This joyful event, just a few years after the Civil War, highlights how quickly the immigrant community had grown and organized cultural life on the hill.

Building a Community: Churches, Schools, and Social Life

Faith and education were cornerstones of Troy Hill’s community-building. In 1848, German Catholics in Allegheny City (the independent city that encompassed today’s North Side) founded St. Mary’s Church to serve German-speaking parishioners . But as more Germans moved up to Troy Hill – a “rather rural area beyond the borders of Allegheny City” – it became clear they needed a parish of their own in the neighborhood. In 1866, Father John Stibiel, pastor of St. Mary’s, helped organize a new Troy Hill parish. That year on May 1 (May Day), Pittsburgh’s Bishop Michael Domenec purchased ten lots of hilltop land as the site for a church to serve Troy Hill’s Germans . The chosen location, near today’s Troy Hill and Claim Streets, was so central that local lore joked the name “New Troy” came from the landowner’s connection to Troy, NY .

By August 1866, the congregation was formed and construction began on the church. Parishioners – many of them butchers, carpenters, and laborers – lent their sweat to build it, as the community lacked wealthy benefactors . In June 1868, the modest but lovely Most Holy Name of Jesus Church was dedicated, becoming the spiritual heart of Troy Hill . That summer’s dedication was a grand affair (likely coinciding with the Saengerfest mentioned earlier), complete with festivals and music. During the ceremony, the Bishop announced that a Belgian-born priest named Father Suitbert G. Mollinger would become Troy Hill’s first pastor . This appointment would have profound implications for the neighborhood’s future.

Alongside the church, education quickly followed. As early as 1836 – even before the parish – a tiny one-room public schoolhouse had opened on Troy Hill (then called Mount Troy School No. 1) to serve the handful of local children . That simple 24×36-foot brick school was replaced in 1860 by a two-room school as the population grew . After the Civil War, enrollment swelled to nearly 200 pupils, forcing expansions in 1874 . By 1885, Troy Hill, now part of Allegheny City’s school system, built a larger four-room schoolhouse to keep up with its growing brood of students . Education was a priority for these immigrant families, and they took pride in their neighborhood school. (Eventually, in 1907 a grand new Troy Hill School would be built, serving the community until 1960 .)

Church and school weren’t the only institutions. German Troy Hillers formed social clubs, singing societies, and volunteer groups, weaving a rich social fabric. The Gesangvereins (singing clubs) held regular concerts and festivals – like that 1868 Saengerfest – which drew visitors from all over Allegheny City. The isolation of the hilltop fostered a strong community bond. Neighbors helped raise each other’s barns and churches, shared in celebrations, and supported each other in times of need. A century later, author Clare Ansberry would note this “unusual loyalty” among Troy Hillers, describing how living on that “sliver of land” made them “remarkably self-sustaining”, always “comforting one another in grief” and “passing flowers over a fence” in daily acts of kindness . This close-knit character has deep roots in the 19th-century village life of Troy Hill.

Father Mollinger and the Shrine on the Hill

No history of Troy Hill would be complete without Father Suitbert Godfrey Mollinger, the eccentric Belgian priest whose legacy still draws visitors to the neighborhood. Father Mollinger arrived as pastor of Most Holy Name Parish in 1868, finding a humble congregation of about 70 families scattered among woods and fields on Troy Hill . He came from nobility – born in 1830 to a wealthy family in Belgium – and had even trained in medicine before entering the priesthood . This unusual background made him both a spiritual leader and a sort of doctor for the community. Mollinger’s wealth far exceeded that of his flock (who were mostly farmers, butchers, and railroad workers), yet he poured much of his inheritance into the parish .

Within weeks of his arrival, Father Mollinger had set up a small parish school in the back of the church, personally funding its needs . He built a grand new rectory in 1877 – a Second Empire style mansion on Harpster Street that stood out among the modest workers’ homes . This elegant residence, complete with stained-glass windows and a gilded dining room, signaled that Troy Hill had a rather extraordinary priest ! But Mollinger was beloved not for his riches, but for his compassion: he gained fame throughout Pittsburgh as a healer, dispensing medicines and prayers to the sick who climbed the hill seeking his aid .

Mollinger’s lasting monument is St. Anthony’s Chapel, a treasure of Troy Hill and indeed all of Pittsburgh. Around 1860, before coming to Troy Hill, he had begun collecting sacred relics – the physical remains of saints and martyrs. By the 1870s, his collection had grown sizable and needed a proper home. In 1880, after a trip to Europe to acquire more relics, Father Mollinger proposed building a new church for the parish that could also house his holy collection . The parish committee balked at the cost, so Mollinger resolved to finance it himself . On a plot adjacent to the rectory, he built a personal chapel dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua. The original chapel, completed in 1880, was modest in size – basically today’s sanctuary and front part of the nave – but it was soon filled with hundreds of relics encased in ornate reliquaries.

Over the next decade, Mollinger didn’t stop. He acquired life-sized wood-carved Stations of the Cross from Munich and in 1890 paid to expand the chapel, lengthening the nave to fit these dramatic statues . He installed a grand altar, imported an organ and bells, and made the chapel a stunning example of Gothic Revival architecture. By 1892, St. Anthony’s Chapel was ready to be revealed to the world. On June 13, 1892 – St. Anthony’s feast day – thousands of people ascended Troy Hill for the chapel’s dedication Mass . It was to be Father Mollinger’s triumph; pilgrims came hoping to be healed by the renowned priest-doctor. Tragically, that very morning Mollinger suffered a medical collapse (an attack of “dropsy”) after the first Mass . Two days later, the beloved priest died, shockingly on the cusp of realizing his dream. Mourners crowded the hill for his funeral, grieving the man who had given Troy Hill so much .

Father Mollinger’s legacy lives on in Troy Hill. St. Anthony’s Chapel remains one of the most extraordinary sacred sites in the U.S., home to over 5,000 relics – the largest collection outside of the Vatican . Visitors today can see items ranging from bones of apostles to a fragment of the True Cross. The chapel’s unassuming exterior belies the spiritual treasure inside, making it a true hidden gem of the neighborhood . Parishioners still hold regular Mass and tours there, keeping alive the tradition that began with Father Mollinger’s devotion. (For more on this remarkable shrine, see Historic Churches in Pittsburgh: The City’s Oldest and Most Beautiful Cathedrals, which features St. Anthony’s Chapel among Pittsburgh’s greatest religious landmarks.)

Hard Work on “Pig Hill” and Beyond

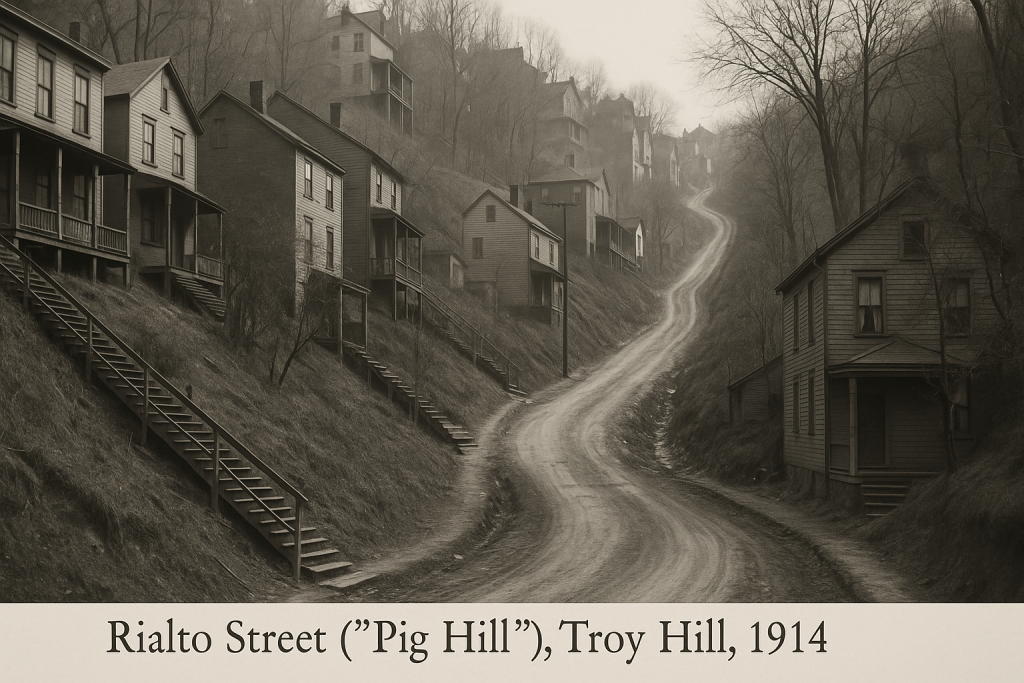

In its 19th-century heyday, Troy Hill was a blue-collar enclave. Most residents toiled in the industrial and commercial enterprises down along the river and in adjacent districts. Men worked as butchers, tannery hands, brewers, railroad men, and laborers, while many women found work at local factories like the sprawling Heinz food plant nearby . Each day, these workers would descend and later climb the steep hill – there were no easy commutes! One legendary path was Rialto Street, a dizzyingly steep road that connects Troy Hill to the riverfront. With a 24% grade, it ranks among Pittsburgh’s steepest streets . Locals nicknamed it “Pig Hill”, and for good reason: in the 1800s, herds of squealing pigs were driven up Rialto Street from the stockyards on Herr’s Island (a river island at the hill’s base) to slaughterhouses in Spring Garden . Residents grew accustomed to the daily porcine traffic jams – imagine dodging pigs on your walk home!

The industries surrounding Troy Hill were integral to its identity. Just downhill in Deutschtown (East Allegheny) rose the Eberhardt & Ober Brewery (est. 1848), one of Pittsburgh’s biggest breweries – in fact, the Victorian brewery buildings still stand today as part of the Penn Brewery complex . Troy Hill’s John P. Ober, the brewery’s president, even built a fancy Stick Style mansion on Lowrie Street in 1877 (known as the Ober-Guehl House) . In nearby Spring Garden, smoke from tanneries and meatpacking plants often wafted up to Troy Hill. And just across the river on Herr’s Island (also called “Stockyard Island”), thousands of livestock met their end to feed the growing city – giving the area a less-than-rosy aroma in the summer. Many Troy Hill residents worked there and in the warehouses by the river.

One employer in particular became famous: the H. J. Heinz Company. Heinz’s main factory, opened in the 1890s along River Avenue, was a massive complex making ketchup, pickles, and other foods . For locals, Heinz was more than a company – it was an opportunity. “Pickle packer” was a common job title for Troy Hillers (many women found work bottling Heinz’s famous pickles), and Heinz’s cleanliness and worker benefits were well known . It’s fitting that a modern Troy Hill café, Pear and the Pickle, takes its name partly from this history – “Pickle” nods to the Heinz plant, and “Pear” to old pear orchards that once grew where Rialto Street runs . These little details show how deeply work and daily life on Troy Hill were intertwined with the industries of Pittsburgh.

Despite the hard labor, residents built a rich cultural life. They celebrated Oktoberfests and church feasts, formed ethnic clubs, and patronized local taverns after a long day’s work. By the late 1800s, Troy Hill had several beer gardens and saloons, where one could hear German toast “Prosit!” echoing on a summer evening. It was said you could find everything from a good wurst to a good waltz on Troy Hill back then. The community’s diversity also began to widen. While Germans remained the majority, other groups found a home here too. In the 1890s, Czech (Bohemian) immigrants settled on the western edge of Troy Hill, an area that earned the moniker “Bohemian Hill” . Polish and Slovak families moved in, and even a few Irish and Italians over time. Each group brought its own traditions, but instead of forming divisions, Troy Hill’s mix of cultures “gave them the opportunity to embrace one another’s diversities.” The neighborly spirit bridged ethnic differences, united by shared schools, churches, and American-born children.

Bridges, Inclines, and City Connections

For much of the 19th century, Troy Hill felt geographically isolated – a hilltop hamlet separated from Allegheny City by steep slopes. But gradually, infrastructure improved the connections. A wooden wagon bridge over a ravine here, a flight of city steps there, and people had easier access. The biggest change came with the introduction of a Troy Hill Incline in the late 1880s. In 1887, the neighborhood welcomed an incline plane (funicular) that carried passengers up and down the bluff to the streetcar lines below . This incline – the first and only one on the North Side – was a boon for commuters and students. Its upper station sat at 1733 Lowrie Street, and the incline saved many a resident from trudging up “Pig Hill” on foot .

However, the Troy Hill Incline proved short-lived. It struggled financially and, after only about a decade of service, shut down in 1898 . The tracks were later removed, though the little incline station house remains as a historic structure today . Even without the incline, by 1900 Troy Hillers could hop on streetcars and trolleys that looped through the North Side. Pittsburgh Railways ran the #4 Troy Hill trolley until 1959, which trundled along the hill’s narrow streets and down into town . The end of the trolley era in ’59 marked the beginning of car reliance – and once again highlighted Troy Hill’s relative seclusion, as navigating those tight, steep streets by car is not for the faint of heart!

Administratively, Troy Hill also went through big changes. In 1877, Allegheny City (which Troy Hill had joined in 1868) annexed the hilltop officially into its city wards . Troy Hill became the 13th Ward of Allegheny, bringing city services like police, fire, and schools. Then, in 1907, the once-independent Allegheny City was annexed by Pittsburgh in a controversial move (often dubbed “The Great Annexation”) . Overnight, Troy Hill became part of the City of Pittsburgh – specifically, it was folded into Pittsburgh’s new 24th Ward . This municipal shake-up was momentous. Allegheny’s residents had fiercely opposed losing their city status , but in the end Pittsburgh prevailed, absorbing Allegheny and its neighborhoods like Troy Hill (see The Rise and Fall of Allegheny City for the full dramatic story of that annexation). For Troy Hillers, life went on much as before, but now they were Pittsburghers officially, with their addresses and school system changed accordingly.

The early 20th century saw Troy Hill maturing but also facing challenges. The Troy Hill Fire Station #39 opened in 1901 at Froman & Ley Streets – a handsome red-brick firehouse that is now a local historic landmark . The neighborhood’s six iconic landmarks also include the aforementioned St. Anthony’s Chapel, the Most Holy Name Rectory, the Ober-Guehl House, the Troy Hill Incline Station, and the old Allegheny Reservoir Wall (a massive stone retaining wall built in 1848 for a city water reservoir that once occupied the hilltop) . These sites, many now on historic registries, reflect the era when Troy Hill was flourishing.

Yet as Pittsburgh’s industries boomed and then later bust, Troy Hill felt the ripple effects. The neighborhood remained a working-class stronghold through the World Wars and into the 1950s, populated largely by the descendants of the original German families, plus newer Polish and Eastern European residents. It wasn’t unusual in, say, 1940, to hear both English and German spoken on Lowrie Street, or to find multiple generations of the same family living just a few blocks apart.

Mid-Century Changes and Challenges

By the mid-20th century, Troy Hill, like many Pittsburgh neighborhoods, faced headwinds. The post-war suburban exodus drew some younger families out to greener pastures. Steel mills and factories began to downsize by the 1970s, affecting employment. The closure of Heinz’s main North Side plant in the late 20th century (after 110+ years of operation) was a symbolic blow – though Heinz left behind a cleaned-up complex now repurposed for offices and apartments. Troy Hill’s population shrank from its peak mid-century numbers. Houses that once teemed with big families grew quiet as children moved away. Many of the rowhouses and narrow homes, however, stayed within extended families or were passed to new waves of residents, keeping the community fabric intact.

Infrastructure changes also altered Troy Hill’s environment. The construction of modern highways, like Route 28 along the Allegheny River below, meant easier car access but also led to the demolition of some nearby landmarks – notably the St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church at the foot of Troy Hill, which was the first Croatian parish in America (founded 1894) . St. Nicholas Church’s closure and eventual demolition in 2013 for road expansion was mourned by many, including Troy Hillers who remembered its hilltop Grotto overlooking the highway. Meanwhile, Herr’s Island underwent a dramatic transformation in the 1980s-90s from grimy stockyards to the upscale Washington’s Landing marina and townhouses – a sign of Pittsburgh’s economic shift away from heavy industry.

Through these changes, Troy Hill’s strong sense of community proved to be its lifeline. The neighborhood’s social core continued to revolve around the parish and volunteer organizations. In the 1980s and 90s, block parties, church festivals, and civic club events kept community ties strong even as the population aged. A group of devout women became local legends for their acts of service – bringing Communion to the sick, tending to the relics in St. Anthony’s Chapel, and looking after neighbors. (These inspiring ladies were chronicled in the book The Women of Troy Hill: The Back-Fence Virtues of Faith and Friendship by Clare Ansberry, highlighting how ordinary people sustained the neighborhood through tough times.) Indeed, Troy Hill’s relative seclusion acted as a double-edged sword: it discouraged outside investment for many years, but it also insulated the community, fostering a “small town” atmosphere where everyone knew each other.

Troy Hill Today: Pride and Revival

In recent years, Troy Hill has experienced a gentle revival, blending new energy with old traditions. Its German heritage is still celebrated – you’ll find North Siders with surnames like Reinemann, Eberhardt, and Schmidt whose ancestors built this place. The Holy Name parish (now part of a multi-parish grouping) continues to hold an annual festival and Mass in German on special occasions. And of course, St. Anthony’s Chapel draws visitors from around the world, some seeking spiritual solace, others simply marveling at the 5,000 relics and life-sized statues. This quiet, unassuming neighborhood still “lives on through citizens who celebrate their rural, German heritage”, as one community member put it .

At the same time, new life has arrived on Troy Hill. Young families and professionals have discovered the hill’s affordability and character, moving into renovated rowhouses next door to long-time residents. A few trendy businesses have popped up: the Pear and the Pickle café (part corner store, part coffee shop) is a beloved meeting spot for locals old and new . An upscale-yet-homey restaurant, Scratch Food & Beverage, opened at the neighborhood’s central intersection, showing that Troy Hill can sustain a foodie presence . There’s even a touch of the avant-garde – since 2013, several houses on Troy Hill have been converted into immersive art installations by international artists (sponsored by local art patron Evan Mirapaul) . This “Troy Hill art house” project has made the neighborhood quietly famous in contemporary art circles, proving that creativity finds fertile ground here.

Crucially, the spirit of community remains as strong as ever. Neighbors still look out for one another on this hilltop. On a summer evening, you might see children playing at the Troy Hill Spray Park (once the site of the old reservoir) near the looming “Great Stone Wall” that kept water for old Allegheny . You might hear the church bells of Most Holy Name ringing out over the rooftops, or catch the aroma of someone grilling sausages in their backyard. Longtime residents swap stories with newcomers about the days when pigs ran up Rialto or how Volunteer Fire Company picnics used to draw the whole community. The view from Troy Hill – overlooking downtown Pittsburgh’s skyline and the winding Allegheny River – is as grand as ever, a reminder of why people settled here in the first place.

As one of Pittsburgh’s “Neighborhoods of the North Side”, Troy Hill has managed to retain a village-like feel while the big city grew around it. Its rich history is written in its very streets: Lowrie, Hatteras, Claim, Goettman – each name harkening back to a story or family from the past. From its frontier-era land grants to its German immigrant enclave phase, through industrial boom and contraction, and into a 21st-century blossoming of art and community gardens, Troy Hill’s journey is a remarkable one. It stands today as a testament to the endurance of local heritage. The people of Troy Hill – past and present – have shown that even a small hilltop neighborhood can leave a mighty imprint on the tapestry of a city’s history.

Historic Landmarks of Troy Hill: Today, six properties in Troy Hill hold City of Pittsburgh historic landmark status , reflecting the neighborhood’s architectural and cultural significance:

- St. Anthony’s Chapel (1880): Father Mollinger’s relic-filled chapel on Harpster Street, housing the famed collection of 5,000+ relics and life-size Stations of the Cross.

- Most Holy Name of Jesus Rectory (1878): The grand Second Empire-style rectory on Harpster Street that Father Mollinger built, a striking contrast to the surrounding workers’ houses.

- Troy Hill Firehouse (1901): A former fire station at Froman and Ley Streets with a distinctive corner turret; no longer active as a fire hall, it now serves city functions.

- Troy Hill Incline Station (1887): The upper station house of the old incline on Lowrie Street. Though the incline closed in 1898, this quaint building remains as a reminder of the era of inclines.

- Allegheny Reservoir Wall (1840s): A massive stone retaining wall, visible near Cowley Street, which once bordered the Allegheny City Water Reservoir that sat atop Troy Hill in the 19th century.

- Ober-Guehl House (1877): The former home of brewer John P. Ober at 1501 Lowrie Street, a rare example of Victorian Stick Style architecture in Pittsburgh, highlighting the prosperity of some 19th-century residents .

Each of these sites offers a tangible link to Troy Hill’s past – be it faith, public service, infrastructure, or industry – and efforts by local preservationists have helped ensure they survive for future generations to appreciate.

Conclusion

From a forested ridge to a thriving German Catholic village, and from an industrious urban enclave to a community redefining itself in modern times, Troy Hill has traveled a long road through history. Its story is enriched by immigrants seeking a new life, by visionary leaders like Father Mollinger, and by everyday folks whose pride in their neighborhood never wavered. The hill may be small, but the tales are grand – of torchlit festivals, of pig-driven streets, of churches filled with sacred relics, and of neighbors who embody the very definition of community. In Troy Hill, Pittsburgh’s past is always present, perched high on that plateau, looking out over the city it has faithfully served and shaped. This proud neighborhood’s history continues to live on in its streets, landmarks, and, most of all, its people – the true keepers of Troy Hill’s enduring legacy.