Introduction: A City of Steel and Shadowy Schemes

Pittsburgh’s image has long been defined by its steel mills, smoky skies, and hardworking communities. Yet behind the forge and furnaces lurks a parallel history of audacious heists, gritty gangsters, and headline-grabbing crimes. From the mud-caked streets of the 1800s frontier town to the bustling industrial metropolis of the 20th century and beyond, Pittsburgh has witnessed criminal capers as dramatic as any Hollywood screenplay. These true tales – of bandits who blew up armored cars, gangsters who turned city cafés into war zones, and an unlikely thief who plundered a library’s treasures – have become the stuff of local legend. In this journey through Pittsburgh’s underworld past, we’ll explore the most famous heists and crimes that shook the Steel City, uncovering the colorful characters, historical context, and lasting impact of each saga. Prepare to step into the shadows of Pittsburgh history, where every cobblestone and alley might hide a story of intrigue or infamy.

Gilded Age Crime and Chaos (19th Century)

Long before organized crime syndicates or bank security vaults, Pittsburgh’s early decades saw their own brand of lawlessness. In the mid-1800s – when the city’s wealth from coal and iron was rising – crimes of greed and desperation occasionally made lurid headlines. One notorious case in 1857 involved a grisly double murder in Glassport, then a rural village on Pittsburgh’s outskirts. Charlotte Jones, a young woman, conspired with her lover Henry Fife to rob and kill her own aunt and uncle, a reclusive couple rumored to have hidden wealth . In a dark twist, Jones falsely accused an innocent man, Monroe Stewart, of the crime. Stewart was nearly executed alongside Jones and Fife before her last-minute gallows confession exposed his innocence . Though spared the hangman’s noose, Stewart tragically died of smallpox in jail just weeks after his exoneration – a haunting footnote to a case that revealed the rough edges of frontier justice.

A decade later, the city was rocked by the deeds of Martha Grinder, dubbed the “Pittsburgh Poisoner” or even the “Pittsburgh Borgia” in the press. By the 1860s, this seemingly ordinary housewife carried out a chilling poisoning spree using arsenic, targeting acquaintances and boarders for reasons that still remain murky. Grinder was eventually caught, confessed to multiple killings, and in 1866 she was hanged in Pittsburgh – making her one of America’s earliest documented female serial killers . Her crimes, sensationalized in newspapers, gave Pittsburgh a macabre claim to fame during the Victorian era.

Even political turmoil spilled into violence. During the 1892 Homestead Steel Strike – a pivotal labor conflict in the region – an anarchist named Alexander Berkman traveled from New York with a deadly mission. As steel magnate Henry Clay Frick sat in his Downtown Pittsburgh office, Berkman burst in, shot Frick twice and stabbed him, in a radical attempt to assassinate one of industrial capitalism’s most notorious figures . Miraculously, Frick survived the July 1892 attack and defiantly returned to work within days; Berkman was arrested and sentenced to 22 years in prison . The failed assassination shocked the nation – it underscored how Pittsburgh, the heart of America’s industrial might, could also breed extreme resentment and crime amid its labor wars.

By the turn of the 20th century, Pittsburgh had already seen everything from murderous family plots to deadly poisoners and anarchist attacks. These Gilded Age crimes, though often overshadowed by the city’s later gangsters and bank robbers, set the stage for Pittsburgh’s complex identity. It was a city of booming industry and opportunity, but also one where human passions – greed, revenge, desperation – occasionally erupted into infamy. As Pittsburgh grew into a modern metropolis, its crime stories would only become more sensational, keeping pace with the city’s own rapid transformation.

The Biddle Brothers’ Jailbreak Romance (1902)

At the dawn of the 20th century, Pittsburgh was captivated by the saga of Ed and Jack Biddle – the “Biddle Boys” – a pair of bandit brothers whose exploits seemed torn from dime novels. Raised in rough-and-tumble Sharpsburg, the Biddle brothers graduated from petty theft to bold armed robberies amid the prosperity and corruption of Gilded Age Pittsburgh . By 1901, they had assembled a small gang and embarked on a crime spree across western Pennsylvania, targeting businesses and even a bank. Their luck ran out when a determined Pittsburgh detective, Charles “Chal” Schwab, tracked them to a small hotel. Cornered, the Biddles shot the detective dead, instantly elevating their crimes to the level of capital murder . After a massive manhunt, Ed and Jack were captured, convicted of murder, and sentenced to death at the Allegheny County Jail (grimly nicknamed “The Bastille” at the time) . It seemed the brothers’ fate was sealed – until an unlikely love affair turned the tale into front-page news across America.

The twist came in the form of Kate Soffel, the soft-spoken wife of the Allegheny County Jail warden. Kate visited prisoners as part of her charitable duties, but in Ed Biddle she found more than a soul to reform – she found romance. Swayed by Ed’s charisma and desperate plight, Mrs. Soffel decided to aid the brothers in a daring escape. In late January 1902, she smuggled saws and guns into the jail, hidden under her voluminous Victorian skirts . In the pre-dawn hours of January 30, 1902, the Biddle Brothers broke out. With Kate’s help, they slipped past guards and fled into the snowy streets, igniting one of the biggest manhunts in Pittsburgh history.

The unlikely trio’s getaway had an almost cinematic quality. They hopped on a streetcar heading north and rode it to the end of the line, then stole a horse and sleigh from a farm to continue their flight through the winter countryside . Bundled against the January chill and armed with a pilfered revolver, the Biddles and Mrs. Soffel aimed to evade capture long enough to cross the border into Canada. Along the way, the fugitives even stopped at a rural inn (the Stevenson Hotel on Butler Plank Road) to warm up, have a meal, and let their horse rest – as if three people on the lam could momentarily play the role of ordinary travelers.

Their freedom was fleeting. The very next day, a posse of Pittsburgh police and detectives – led by the famed detective Charles “Buck” McGovern – caught up with the sleigh on a road near Butler County . A dramatic gunfight erupted in the snow. When the smoke cleared, both Ed and Jack Biddle lay gravely wounded, each shot by pursuing officers . Kate Soffel, wounded but alive, had tried to shield Ed during the shootout. The Biddle brothers died from their injuries shortly after their capture, ending their brief chapter of freedom in bloodshed. Mrs. Soffel survived to face justice: she was returned to Pittsburgh in chains, convicted of aiding the escape, and sentenced to two years in prison for her role .

The city – and the nation – were enthralled by the Biddle Boys saga. Newspapers printed daily updates during the chase, and crowds gathered outside the jail and courthouse to catch a glimpse of the “fallen” warden’s wife. Kate Soffel, with her prim Victorian manners and shocking choices, became a media sensation. After serving her sentence, she attempted to capitalize on her infamy, joining a touring vaudeville show where she acted out (of all things) her own life story on stage . Pittsburgh’s first major crime celebrity, Kate would live quietly in the city for years afterward, but the legend of the Biddle Boys endured. In fact, their story was so sensational that it inspired a Hollywood film (“Mrs. Soffel,” 1984) many decades later.

The Biddle brothers’ tale has all the elements of an enduring Pittsburgh legend: desperate outlaws, a star-crossed romance, a daring jailbreak, and a final blaze of gunfire. More than a century later, the very sleigh used in their escape sits preserved in the Heinz History Center – a tangible relic of a time when Pittsburgh’s newspapers rejoiced in calling the Biddles the city’s “most notorious outlaws.” They remain folk heroes of a sort, symbolizing a rebellious streak in Pittsburgh’s history and reminding us that truth is sometimes stranger (and more dramatic) than fiction .

The Great Castle Shannon Bank Robbery (1917)

As Pittsburgh barreled into the modern age of automobiles and telephones, a group of immigrant robbers orchestrated a heist that reads like a dark Keystone Kops comedy – equal parts deadly and absurd. The setting was the usually quiet borough of Castle Shannon, a coal-mining town just south of the city. On May 14, 1917, four Eastern European immigrants – led by a Russian laborer named Mikhail Titov – put into motion an elaborate plan to rob the town’s only bank . What followed was one of the bloodiest bank robberies in Pittsburgh history, complete with a wild chase involving angry townsfolk in a commandeered hearse.

Titov and his crew (John Tush, Sam Barcons, and Haraska Garason) had carefully scoped out the First National Bank of Castle Shannon. They arranged a getaway car by hiring a local driver, Nick Kemanos, to ferry them around for the day – not telling him his brand-new Maxwell automobile was about to become a getaway vehicle . On the chosen afternoon, the gang loaded into the Maxwell (after fortifying themselves with a few swigs of liquid courage at a saloon en route ) and rolled into Castle Shannon. They parked on a side street, pulled black bandannas over their faces, and approached the bank with guns drawn. Inside were two bank employees and a lone customer. In a stroke of luck (or misfortune) for the outlaws, the customer spoke Russian, which allowed the robbers to bark orders in their native tongue . The tellers, however, were not so compliant – one, Frank Erbe, had a premonition of trouble that morning and actually brought a revolver to work. As soon as the robbers announced the stickup, Erbe dove behind a desk and opened fire .

What ensued was absolute chaos in the small bank lobby. The robbers, likely a bit tipsy and certainly on edge, returned fire wildly. Erbe was hit five times and collapsed, mortally wounded . The head cashier, Daniel McLean, stepped out of the vault at the wrong moment and was immediately shot between the eyes – he died instantly, still clutching a heavy ledger book . Within moments, both bank employees were down, and the robbers seized their chance to grab every dollar in sight. Stuffing roughly $17,000 in cash (a huge sum in 1917) into sacks, the four thieves bolted out the door and ran for their getaway car.

But their carefully laid plan began to unravel almost immediately. The gunfire had alerted the entire neighborhood – and Castle Shannon was the kind of town where nearly everyone had a firearm (and a sense of frontier justice). As the bandits fled, armed townspeople emerged from shops and homes, ready to form an impromptu posse. The local justice of the peace, “Squire” George Beltzhoover, even snatched up someone’s shotgun and confronted the robbers as they reached the street . He pulled the trigger at the fleeing men… only to realize the shotgun wasn’t loaded. In a scene almost out of a slapstick film, the frustrated squire then threw the gun at the criminals. Two of the robbers (Barcons and Tush) promptly tackled Beltzhoover and, in a fit of rage, smashed him in the face with a sack filled with silver coins, breaking his nose and knocking him flat . While the townspeople tended to the dazed squire, the gang split up. Barcons and Tush took off on foot toward the nearby woods, and Titov and Garason ran back to the Maxwell where their driver Kemanos waited.

A furious chase played out through Castle Shannon’s unpaved streets. As Barcons and Tush sprinted toward the wooded Castle Shannon Golf Course, a group of armed citizens trailed them. Cornered and seeing no escape, the two robbers made a grim decision: they attempted a double suicide rather than be captured. Tush managed to shoot himself dead, but Barcons’ attempt misfired – literally. He put his pistol in his mouth and pulled the trigger, only to mangle his face without killing himself . When the pursuing vigilantes arrived, they found Barcons alive (albeit missing a chunk of his jaw). Enraged at the carnage the gang had caused, some townspeople murmured about lynching the injured bandit on the spot . Cooler heads prevailed, and Barcons was taken into custody – badly wounded, but lucky to be alive.

Meanwhile, Titov and Garason’s getaway took a comedic turn. Reaching the Maxwell, they roused Kemanos – who had dozed off behind the wheel, oblivious to the gunfight – and shouted at him to step on it . The Maxwell roared off toward Pittsburgh. The delayed posse, having lost the other two robbers, then scrambled to find a vehicle to chase the fleeing car. In a twist worthy of an action movie, the only vehicle they could find was the local undertaker’s hearse, which they promptly commandeered. Within minutes, a posse of eleven armed men piled into the funeral coach and tore off down the road in hot pursuit . Imagine the sight: a speeding hearse careening through the streets, full of townsfolk with rifles, horn blaring as it chased the bandits!

The hearse thundered down the road through neighboring towns, and incredibly, it began to gain on the Maxwell. After a few miles of chase, the posse caught up – only to find the Maxwell cruising along with no robbers inside. A bewildered Kemanos explained that Titov and Garason had leaped out of the car a few miles back, disappearing on foot into the woods when they realized they were being pursued . The two ringleaders – and roughly half of the loot – simply vanished. Despite a region-wide manhunt, Titov and Garason were never seen again. Some speculated they hopped freight trains or even managed passage to Europe; local legend imagines them slipping back to Russia with pockets full of Pittsburgh cash, though considering Russia was in the throes of revolution in 1917, their ultimate fate is anyone’s guess .

The aftermath brought only partial justice. Roughly half of the stolen $17,000 was recovered from the captured Barcons and the deceased Tush . Barcons, once healed, stood trial and was convicted of murder – he met his end in Pennsylvania’s electric chair a couple years later . Nick Kemanos, the hapless driver, insisted he had no idea his passengers planned a robbery. He was acquitted of one murder but convicted of the other (since two bank employees died) – a legal tangle that was still on appeal when Kemanos died of the influenza pandemic in jail in 1918 . The Castle Shannon community, having lost two respected citizens in the robbery, grieved but also grimly celebrated their own defense: ordinary townsfolk had stood up to violent criminals (if somewhat clumsily), embodying a vigilante spirit.

In retrospect, the Castle Shannon bank robbery is remembered both for its tragic cost – five lives lost (two bank employees, one robber by his own hand, and later two more by execution and illness) – and for its almost farcical elements. Newspapers at the time recounted the episode with a mix of horror and dark humor, amazed at the bizarre twists. A century later, local historians still talk about the day a sleepy little mining town turned into the set of a Wild West showdown, complete with a heroic (if unlucky) bank teller, a high-speed hearse chase, and a bag of silver dollars wielded as a weapon. It remains one of the most famous heists in Pittsburgh history, and certainly one of the most unbelievable.

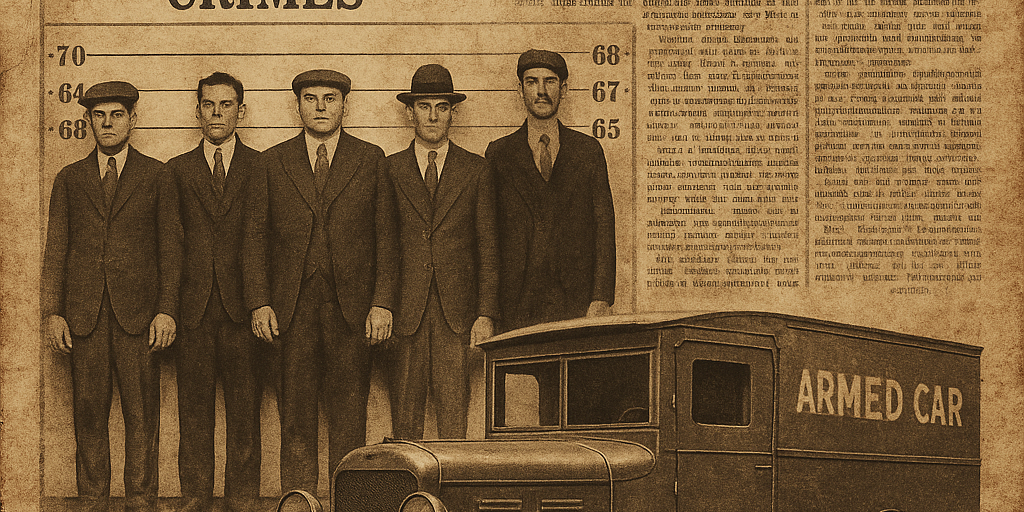

Broad Daylight on Federal Street: The Boggs & Buhl Holdup (1921)

The 1920s dawned as a prosperous time for Pittsburgh – the Roaring Twenties brought economic boom and bustling commerce. But with prosperity came brazen criminal opportunities. Perhaps nothing illustrates this better than the Boggs & Buhl robbery of 1921, a caper so bold it unfolded in broad daylight on a busy North Side street, turning an ordinary Friday afternoon into a scene of panic. Boggs & Buhl was a famous department store on Federal Street in old Allegheny City (today Pittsburgh’s North Side). On June 10, 1921, around 1:30 p.m., two store employees were walking the day’s earnings to the bank when three armed bandits jumped out of a car and ambushed them . What happened next could have been lifted from a silent film thriller – gunfire, a downtown chase, and a narrow brush with death that Pittsburghers would recount for decades.

The holdup was meticulously timed. As the two employees – carrying the store’s bank deposit in satchels – stepped onto the sidewalk outside Boggs & Buhl, a touring car screeched to a halt and three men leapt out with pistols drawn. They demanded the money at gunpoint, sending pedestrians scattering in fear. One of the employees resisted and was pistol-whipped; another robber grabbed the deposit bag. In the scuffle, one store employee was shot and wounded . The audacity of firing a gun on a crowded city street in midday sent people ducking behind lamp posts and market stalls.

At that very moment, fate intervened in the form of Charles H. Schultz, an off-duty Pittsburgh police patrolman who happened to be on Federal Street. Schultz was in plainclothes and unarmed save for his personal revolver – but he didn’t hesitate. As the bandits rushed back to their getaway car, Schultz confronted them head-on in the street. One of the robbers leveled his gun at the officer and pulled the trigger. Miraculously (or luckily), the bullet merely pierced the felt of Officer Schultz’s hat, grazing it with four holes but missing his skull . In an image that splashed across newspaper front pages the next day, Schultz later showed his ruined gray fedora, Swiss-cheesed by bullets, to his precinct sergeant – dramatic proof of just how close he came to death . Despite literally having bullets whistle through his hat, Schultz tackled one of the fleeing gunmen, wrestling him to the ground in a fury of fists and gunshots.

A chaotic street battle ensued. The other robbers fired wildly as panicked bystanders dove for cover. Federal Street, typically bustling with shoppers from the market, became an impromptu battlefield. Schultz managed to hold one bandit down, likely preventing his escape. The other two thugs jumped into the idling getaway car – deposit bag in tow – and sped off amid a hail of bullets. One robber leaned out the car window, discharging his pistol to keep pursuers at bay, sending stray rounds into store windows. In the mayhem, a couple of pedestrians suffered minor injuries from either ricochets or the scramble to safety.

The entire episode lasted mere minutes. When the smoke cleared, one suspect was in custody (thanks to Officer Schultz’s heroics), one department store messenger was wounded but survived, and an estimated $33,000 (in 1921 dollars) had been snatched in the bag that got away. The city’s newspapers had a field day. The Pittsburgh Daily Post and Post-Gazette plastered the story and photos of the aftermath across their front pages on June 11, 1921 . The image of Schultz’s bullet-riddled hat became a symbol of both the daring of criminals and the bravery of local lawmen . One paper called the midday heist “unparalleled in the city’s history,” aghast that armed bandits would be so bold as to stage a gunfight on a crowded street .

The Boggs & Buhl holdup was part of a larger surge of crime in the early 1920s – a time when Prohibition and post-war unrest saw robberies spike nationwide. So alarming was this crime wave that in January 1921 (months before the robbery) a former Pittsburgh Police superintendent had publicly urged the creation of a national detective bureau to combat interstate crime sprees . Incidents like the North Side holdup only underscored that need, foreshadowing the rise of the FBI later in the decade. In Pittsburgh, the robbery also had some unexpectedly tender repercussions: just two days afterward, a young girl in Lawrenceville accidentally shot and wounded his sister while they were play-acting “cops and robbers,” explicitly mimicking the Boggs & Buhl crime they’d heard about . (Fortunately, the child survived.) Even kids were touched by the drama, a sign of how these events captured the public’s imagination.

In the end, police tied the captured suspect – and the accomplices who eventually were rounded up – to a wider gang of bank robbers that had been plaguing western Pennsylvania. The arrest of the Boggs & Buhl bandits led to evidence implicating them in other heists from Aspinwall to Swissvale . Pittsburgh’s law enforcement cracked down hard, eager to prove that daylight shootouts on city streets would not be tolerated. The convicted robbers went to prison for long terms, and some measure of order was restored. But the legend of the “downtown daredevils” lived on. For years, the old Northsiders would point to the bullet holes in brick facades on Federal Street and recount how Officer Schultz bravely faced down bandits as traffic and commerce ground to a halt.

The Boggs & Buhl robbery is remembered as a turning point in Pittsburgh’s crime history – a moment when the city realized that big-city style holdups could happen right at home. It combined the roaring excitement of the Jazz Age with an element of Pittsburgh’s own frontier grit. Today, the site of the old department store is just a piece of the modern North Side, but the echoes of those gunshots and the tale of the bullet-pierced hat remain part of Pittsburgh lore, emblematic of an era when crime and courage collided on the city’s streets.

Bootleggers and Bombs: Pittsburgh’s Prohibition Gang Wars (1920s)

No account of Pittsburgh’s infamous crimes is complete without delving into the Prohibition era, when the city’s underworld flourished amid the country’s ban on alcohol. The 1920s saw Pittsburgh transformed into a battleground for bootleggers, rum-runners, and racketeers, as criminal gangs vied for control of the lucrative illicit liquor trade. In neighborhoods like the Hill District and the Strip District, illegal stills and speakeasies popped up behind unmarked doors, and the smell of homebrew wafted through alleyways. What followed was essentially an underground war, with rival mobsters resorting to bombings and brazen murders to eliminate the competition and secure their share of the spoils.

One early Pittsburgh crime boss, Stefano Monastero, made his mark by combining Old World mafia tactics with New World boldness. Monastero, of Sicilian origin, rose to power by the mid-1920s and wasn’t shy about using violence to keep his grip on the bootlegging business. He and his crew allegedly planted bombs at rival distilleries around the region – a literal explosive way to thin out the competition . Turf wars escalated to the point that news of speakeasy bombings or drive-by shootings became alarmingly common in the late ’20s. In 1927, Monastero purportedly orchestrated the assassination of a competing liquor dealer, Luigi “Big Gorilla” Lamendola, eliminating a major rival . It was clear that Pittsburgh’s burgeoning Italian-American Mafia had arrived and was dead serious about controlling the city’s vice.

Yet, in the underworld, fortune is fickle. Monastero’s reign ended as violently as it began. In August 1929, as Monastero and his brother Sam stepped out of St. John’s Hospital in the city (reportedly after visiting a sick associate), they were ambushed by gunmen and riddled with bullets on the sidewalk . The daring double murder – right in front of a hospital – signaled that the Mafia power structure in Pittsburgh was far from settled. Whodunit? Most suspected the hit was ordered by rivals within the Sicilian underworld, perhaps by allies of the emerging Volpe brothers, another powerful crime family. Pittsburghers reading their morning papers encountered a city aswirl in secret gangland feuds that felt more like Chicago or New York.

Into the vacuum stepped the Volpe brothers themselves. Led by John Volpe and backed by several of his siblings, the Volpe gang rose to prominence by 1932, controlling a significant portion of Pittsburgh’s bootleg alcohol and the related numbers racket (an illegal lottery popular in the city’s African-American neighborhoods) . The Volpes grew wealthy and cocky – John Volpe even drove a custom bulletproof Cadillac around town, flaunting his gangster prestige. Their base was the Rome Coffee Shop at 704 Wylie Avenue in the Hill District, an innocuous café that in reality served as a headquarters for bootlegging deals and payoff meetings . Pittsburgh’s Prohibition scene by the early ’30s was essentially under Volpe rule. But power invites envy, and the Volpes learned the hard way that success made them targets.

The climax of Pittsburgh’s bootlegger wars came on July 29, 1932, a date that still lives in infamy in local crime annals. That summer, the city’s Mafia boss was John Bazzano, who had once been friendly with the Volpes but now viewed them as dangerous rivals encroaching on his turf. Bazzano decided to act decisively. On that July day, as John Volpe stepped outside the Rome Coffee Shop for a midday stroll, a hit squad of gunmen rushed up and opened fire in broad daylight . In a matter of moments, a massacre unfolded on Wylie Avenue: John Volpe and two of his brothers (James and Arthur) were cut down in a hail of bullets, killed on the spot . The Volpe brothers hit was a sensational gangland slaying – three brothers murdered together on a public street, with witnesses diving for cover as the crack of gunfire echoed among the brick facades. Pittsburgh had never seen a Mafia attack this ruthless and conspicuous. The city was shocked, and the Hill District, which had seen its share of violence, was nevertheless stunned by the sheer audacity of the triple homicide.

However, the Volpe massacre was not the final chapter. In the underworld, big moves often have big consequences. The Volpes had allies and answerable higher-ups in the national Mafia network. Word has it that the mob’s National Commission – an assembly of top gangsters from across the country – did not appreciate Bazzano’s unsanctioned slaughter of the Volpe crew (who had connections to influential families). Retribution came swiftly and mercilessly. Just a week after the Wylie Avenue ambush, John Bazzano’s body was discovered in New York, stuffed into a burlap sack. He had been strangled and stabbed over a dozen times, a clear Mafia message that he had crossed a line . Pittsburgh’s reigning mob boss had himself become a victim of the very violence he dealt in. In the span of days, the city’s two most powerful bootlegging factions annihilated each other – a bloody crescendo to the Prohibition era’s chaos.

By the end of 1932, with so many kingpins dead or deposed, the bootleg wars simmered down. And not a moment too soon: in 1933, Prohibition was repealed, making the liquor trade legal again and pulling the financial rug out from under the bootleggers. But the legacy of the 1920s gang wars in Pittsburgh was lasting. They cemented the presence of an organized Italian-American crime syndicate (the Mafia) in the city, which would transition into other rackets (gambling, extortion, etc.) in the decades to follow. They also left a trail of corruption – it was whispered that many police and politicians had been bought off by one gang or another during Prohibition, a claim supported by a few scandalous trials in the ’30s.

For Pittsburgh residents of the time, this era was unforgettable: the sight of blown-up moonshine stills in the suburbs, the sound of Thompson submachine guns rattling in Lawrenceville or the Hill on a dark night, and headlines of mob bosses meeting violent ends. Even today, stories of the Volpe brothers and the Rome Coffee Shop hit are told as a cautionary tale of overreach in the criminal underworld. Prohibition turned ordinary men into millionaires and murderers, and Pittsburgh – the Steel City – earned another, more dubious nickname in those days: “Crime City.” It was an era when the law was often outgunned, and the streets ran with beer and blood.

The Mafia’s Golden Era and Mid-Century Scandals (1940s–1960s)

After the tumult of Prohibition, Pittsburgh’s underworld didn’t disappear – it evolved. With alcohol legal again, organized crime shifted its focus to other enterprises: gambling halls, numbers rackets, loan-sharking, and labor racketeering. The mid-20th century became the golden era of the Pittsburgh Mafia, marked less by public shootouts and more by a tight-knit, quietly prosperous criminal empire. Under the steady hand of bosses like Frank Amato in the 1940s and the legendary Sebastian “Big John” LaRocca from the 1950s into the 1970s, the Pittsburgh crime family consolidated power and often kept a lower profile than the wild days of the ’20s . But even in these relatively subdued decades, a few crimes and capers bubbled into public view, reminding Pittsburghers that the mob was still very much in business.

During these years, the Italian-American Mafia in Pittsburgh entrenched itself in the fabric of the city. They forged friendly ties with politicians, reputedly had Pittsburgh Police on their payroll, and oversaw illegal gambling dens from the Hill District to the Strip District. One popular racket was the “numbers” game – an underground lottery beloved in Pittsburgh’s African American communities. Mobsters like Gus Greenlee (also known for owning the Negro League baseball team the Pittsburgh Crawfords) ran extensive numbers operations, earning fortunes 10 cents at a time from daily bettors. Although Greenlee himself wasn’t LaRocca’s man (he was an independent who had his own run-ins with the law in the 1930s), by the 1940s and ’50s the Mafia family certainly controlled or taxed many such betting operations. Saloons and social clubs quietly hosted high-stakes card games. Union officials, some corrupted, allowed racketeers influence over certain industries. It was a subtler underworld, but a lucrative one.

Now and then, the façade of calm cracked. One famous incident on the national stage was the 1957 Apalachin Conference bust. That year, LaRocca and one of his top men traveled from Pittsburgh to a tiny hamlet in upstate New York for a gathering of major Mafia figures from across the country. The meeting – essentially a national mob summit – was supposed to be secret, but local state troopers suspicious of all the out-of-town luxury cars ended up raiding the get-together. Over 60 mobsters were detained in the woods scrambling to escape, among them Pittsburgh’s own John LaRocca. The incident made headlines coast-to-coast and confirmed what J. Edgar Hoover had long denied: organized crime was a nationwide network, and Pittsburgh had a seat at that table. LaRocca’s embarrassed mug was splashed in papers, and back home the FBI and police leaned in with new intensity. Though LaRocca himself managed to avoid prison (charges from Apalachin were dismissed on a legal technicality), his attendance at that meeting solidified his clout in mob circles and also put a permanent target on Pittsburgh’s mob operations from law enforcement.

By and large, the Mafia in mid-century Pittsburgh preferred to operate in the shadows. But violence still flared when necessary to settle scores or maintain discipline. A case in point: in 1964, a car bombing in the East Liberty neighborhood shook residents – it turned out to be a mob hit on a gambling operative who had crossed the wrong people. Through the ’50s and ’60s, small-scale mob murders occurred, usually within the underworld (so-called “housecleaning” of informants or rivals), but the crime family avoided high-profile public shootings that could spark another crackdown.

One area of public contention was the control of nightlife and gambling. The city’s upscale clubs and downtown casinos (often operating just this side of legality) sometimes got caught in vice raids. In one notable scandal, a highly popular restaurant and cabaret in Downtown Pittsburgh was revealed in the late 1960s to be secretly part-owned by mob figures and hosting rigged casino nights for VIPs. When the news broke, it implicated a few local officials who had accepted lavish “freebies” from the club – a minor corruption flap that embarrassed the city government and hinted at the Mafia’s reach into legitimate businesses.

Perhaps the most impactful crimes of this era, however, were white-collar and political. In the 1950s, Pittsburgh saw a series of corruption cases that toppled police chiefs and brought down a mayor (the 1951 scandal of Mayor David Lawrence’s police chief being indicted for protecting gambling joints, for example). The overlap of organized crime and city hall was an open secret, and periodic investigations (aided by brave journalists) would bring it to light. These weren’t “heists” in the traditional sense, but they were crimes that shaped Pittsburgh’s governance and reputation.

Despite these dramas, the LaRocca family remained intact and extremely wealthy. By the late 1960s, Pittsburgh was known as one of the most orderly Mafia cities – code for the mob running things without much bloodshed or public fuss. LaRocca himself died of natural causes in 1984, after nearly three decades as boss, handing off a smooth-running operation to his successors. But as the mob laid low, other kinds of crime would soon grab Pittsburgh’s headlines, from a breathtaking museum heist to daring modern bank robberies.

In sum, the mid-20th century in Pittsburgh was an era when organized crime went corporate. The bosses swapped Tommy guns for business suits (most had “real” businesses as fronts – LaRocca, for example, ran a vending machine company and a beer distributorship, giving him a veneer of legitimacy ). Yet, under that surface, the graft, gambling, and occasional violence continued. Pittsburgh’s blue-collar elegance in those years – the era of Heinz and Westinghouse prosperity – had a shadow side greased by mob money. And every so often, a news story – a raid, an indictment, a suspicious explosion – reminded the public that the city’s vaunted “most livable” status had come with a compromise: a gentlemen’s agreement between crime lords and the powers that be. This uneasy peace would not last forever, but it carried Pittsburgh’s underworld quietly into the 1980s.

The Great Pittsburgh Armored Car Heist (1982)

If the 19th century had given Pittsburgh stagecoach bandits and the 20th century its share of mob capers, the 1980s delivered a new kind of crime drama – the high-tech, big-money armored car heist. And not just any heist: on St. Patrick’s Day 1982, Pittsburgh became the scene of one of the largest cash robberies in U.S. history up to that time. The target was the Purolator Armored Inc. depot in suburban Brentwood, where millions in currency from local banks and businesses was stored. What unfolded that day remains an astonishing and still unsolved caper, often whispered about in Pittsburgh taverns as the ultimate “one that got away.”

On March 17, 1982, as many Pittsburghers were enjoying green beer and parades, two men were executing a meticulous plan at the Purolator facility. Just after one of the armored trucks departed the depot around 11:00 AM, these two individuals snuck into the building posing as FBI agents, complete with fake badges and a phony story about a “tip” of an impending robbery . The only guard on duty, thinking law enforcement was there to help, let his guard down – a grave mistake. The impostors swiftly overpowered the guard and snatched his shotgun, then handcuffed him and duct-taped his eyes, effectively neutralizing the sole witness . In a stroke of almost cinematic coolness, the fake FBI men used the depot’s own radio system to signal what sounded like an all-clear, calling in their own getaway vehicle to the loading bay.

In mere minutes, the thieves helped themselves to bag upon bag of cash from the vault. They were selective and shockingly restrained: they took about 225 kilograms of currency – roughly $2.5 million worth – and left an astonishing additional $55 million sitting untouched in the vault, presumably because they couldn’t carry more . Even the investigators had to marvel at that detail: the robbers only took what they could manage to haul, like kids in a candy store with only so many pockets. By the time another guard arrived, the two intruders and their van full of money had vanished into thin air.

The precision and daring of the Purolator depot robbery baffled law enforcement. It was pulled off with no alarms tripped, no shots fired, and almost no evidence left behind. It instantly earned the title of “Pittsburgh’s largest heist ever”, and the city was transfixed by the story. The fact that it happened on a festive holiday led some to darkly joke about the “wearin’ of the green (backs).” The FBI and local police launched a massive investigation, but early leads were few. Every known local criminal with the skills or audacity was interrogated. Surveillance footage was scant. The guard who’d been duped could only provide vague descriptions of the culprits. It was, in many ways, the perfect crime – at least in execution.

Months rolled by, then years, with little progress. Speculation ran rampant. Did the Pittsburgh Mafia secretly orchestrate one last grand score before fading out? (Plenty wondered – after all, who else could unload so much cash safely?) . Was it an inside job by current or former armored car employees? The code of silence in the underworld held firm, and the money didn’t resurface in obvious ways. The case went cold. In 1990, a ray of hope: during an unrelated federal trial, an informant claimed that a local mob associate named Eugene “Geno” Chiarelli had masterminded the Purolator heist . This tantalizing tip made headlines – finally, a suspect! But the evidence was flimsy hearsay and never led to charges; many suspected the informant was merely spinning tales for leniency. Officially, Chiarelli was never indicted for the crime. The FBI continued to chase leads into the 1990s, but the trail had largely gone cold.

Four decades later, the 1982 Brentwood armored car heist endures in Pittsburgh lore as a legendary cold case – the robbers never caught, the loot never recovered . It’s estimated that if carefully laundered or invested, that $2.5 million could have quietly multiplied, benefiting criminals now enjoying retirement under assumed names. Or perhaps it was squandered in Las Vegas or sunk into some ill-fated scheme – we simply don’t know. What we do know is that the story still gets people talking. Sit down at a bar in the South Side or Bloomfield, mention the Purolator job, and you’ll hear theories swirl: “I heard one of the guys fled to Europe”, “They say the money’s buried somewhere in the Laurel Highlands”, “My cousin’s friend swears a mob boss paid off the cops to look away”. The mystery is part of its allure.

For Pittsburgh, 1982 proved that even as the old gangs waned, the city could still inspire Hollywood-worthy heists. In fact, the modus operandi of the Purolator robbery – cleverly impersonating authorities, leaving behind mountains of cash due to weight – has been cited in books and TV shows about great American heists . It remains one of the largest unsolved robberies in American history. The guard who was duped eventually recovered from the embarrassment and stayed in security work, albeit with a lifelong lesson learned. And Pittsburgh’s law enforcement got a harsh reminder that even in an era of high-tech alarms and armored trucks, human ingenuity (and deceit) could still find a way to exploit any weakness.

Betrayal on the 31st Street Bridge (2012)

Fast forward to the 21st century, and one might assume the era of Wild West stickups was long over. But Pittsburgh in 2012 found itself again in the grip of a stunning armored car robbery – this time with a tragic, murderous twist that set it apart from the capers of old. The culprit was not an outside gang but an insider – a 22-year-old armored truck guard named Kenneth J. Konias Jr., who decided to execute a one-man, inside-job heist against his own partner and employer. The crime shocked Pittsburgh not only for the bold theft of millions in cash, but for the cold-blooded betrayal at its core.

It was a chilly afternoon on February 28, 2012, when Konias and his partner, 31-year-old Michael Haines, were making their rounds in a Garda armored truck through the city. Their route included stops to pick up cash deposits from places like Rivers Casino on the North Shore and retailers like Macy’s . Nothing seemed amiss to Haines as they went about their routine. But Konias had spent months scheming in secret. He knew that once their collections were done, they’d have a truck brimming with money – and a narrow window of time when he could make his move.

That window came under the shadow of the 31st Street Bridge in the Strip District, around 3:40 p.m. The Garda truck pulled over in what was supposed to be a quick stop before returning to base. Suddenly, Konias drew his firearm and shot his fellow guard Haines in the back of the head at point-blank range, execution-style . Haines had no chance. He died instantly, becoming perhaps the only Pittsburgh heist victim to pay with his life in modern memory. Konias then coolly loaded bag after bag of cash – stuffed with proceeds from the casino and several banks – into his own vehicle. In total, he grabbed about $2.3 million in cash, essentially the day’s haul for the armored truck . Leaving his murdered partner slumped inside the armored car, Konias fled the scene, setting off a frantic police response when Haines’ body was found.

The city was horrified and transfixed in equal measure. Here was a young man from a Pittsburgh suburb (Dravosburg) who seemingly snapped and vanished with a fortune, leaving a trail of heartbreak. A massive manhunt unfolded. Law enforcement quickly discovered Konias had gone home immediately after the murder – incredibly, he drove the loot to his parents’ house and unloaded it there, even pausing to make a few phone calls (including one bizarre call to a friend where he allegedly boasted, “I ****ed up – but I got enough money to live on for the rest of my life” ). By the time police pieced together his movements, Konias had ditched his cell phone near Century III Mall to avoid tracking , switched vehicles, and disappeared.

For two months, Konias was a fugitive. Pittsburgh media ran his photograph daily: a stocky, round-faced young man who, up until that week, had been just another anonymous security guard. Tips poured in with supposed sightings, but Konias proved elusive. It turned out he had fled west, then south. The FBI followed his trail through several states. The breakthrough came in April 2012, when investigators traced Konias to Pompano Beach, Florida. Acting on a tip, FBI agents and local police converged on a modest apartment, and on April 24, 2012 – almost exactly 32 years to the day after the legendary 1980 lottery scandal in Pennsylvania – Konias was arrested without incident. In the apartment with him were hundreds of thousands of dollars of the stolen cash, neatly packed. He had spent some money enjoying the Florida coastal life on the run, but remarkably, much of the $2.3 million was still accounted for . Perhaps he realized it’s hard to launder that much cash as a lone wolf. The rest of the money was recovered from stashes he left with acquaintances (including a friend in Pittsburgh whom he had entrusted some cash to right after the crime).

Back in Pittsburgh, Konias faced the music. In court, the betrayal at the bridge weighed heavily. He had murdered a co-worker – a friend, by many accounts – in cold blood for greed. Konias showed little remorse in proceedings, which further enraged the public. Facing overwhelming evidence, he eventually pleaded guilty to murder, robbery and theft charges to avoid a potential death sentence . The judge gave him what amounted to life in prison, ensuring he’d spend decades behind bars for his heinous act . Michael Haines’s grieving family told the court of their immeasurable loss – a young husband and father who never came home from work because of Konias’s actions.

The 2012 Garda armored car heist stands out as one of Pittsburgh’s most brazen modern crimes. It had the hallmarks of a Hollywood thriller – an insider plot, a violent betrayal, a cross-country fugitive chase – but with the sorrowful reality of a life lost. In the context of Pittsburgh’s crime history, it underscored that even in an age of surveillance cameras and GPS trackers, old-fashioned greed and betrayal can still cause mayhem. It also was a grim bookend to the city’s history of heists: unlike the almost gentlemanly 1982 Purolator robbers who hurt no one, Konias’s crime was steeped in blood, shattering the notion of honor among thieves. Pittsburghers won’t soon forget the image of that armored truck parked under the bridge, its engine idling, one guard dead and the other vanished with the loot – a stark reminder that behind every sensational headline, there are real human consequences.

The Carnegie Library’s Stolen Treasure (1992–2017)

Not all of Pittsburgh’s famous heists were snatch-and-grab jobs or violent stickups. One of the most astonishing thefts in the city’s history was a slow-motion heist that unfolded over 25 years within the quiet, stately halls of the Oakland neighborhood. It wasn’t a bank or an armored car that was targeted – it was the city’s crown jewel of knowledge: the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh’s rare books collection. Over more than two decades, hundreds of rare books, maps, and historic artifacts vanished from the library’s archives, piece by piece, in what would turn out to be an inside job of shocking proportions. By the time the theft was discovered in 2017, it was dubbed “the most extensive library theft in America in at least a century,” with an estimated value of over $8 million .

The stage for this extraordinary crime was the Oliver Room, a secure, climate-controlled haven on the third floor of the Carnegie Library where the institution’s most valuable and rare materials were kept. Protected by heavy doors, alarms, cameras, and strict sign-in protocols, the Oliver Room was thought to be virtually theft-proof . And indeed, its security might have thwarted any ordinary thief. But the perpetrator in this case was no ordinary thief – it was the very person in charge of the room’s security, the archive’s manager, Gregory Priore. Hired in 1992, Priore was a respected archivist with deep knowledge of the collection and the sole key to the kingdom. In a twist worthy of an Agatha Christie novel, he used his intimate access to become the library’s own phantom thief.

For years, Priore pilfered items from the Oliver Room’s shelves, sometimes slicing maps or illustrations out of books, other times making whole volumes disappear. His targets were carefully chosen: incunabula (books from the 15th century), atlases from the Age of Discovery, original Audubon prints – the kind of treasures that would fetch high prices on the antiquarian market . One example was an exceedingly rare 17th-century atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Blaeu Atlas), from which all 276 maps were removed – leaving behind a gutted shell in the library’s archives . For over two decades, nobody noticed these thefts. Priore was cunning, often leaving the empty covers or switching catalog records to mask the missing items. And because he was the authority overseeing that collection, there was little second-guessing. It was an astounding breach of trust: the fox not just guarding the henhouse, but cataloguing which hens might be most valuable to steal.

Of course, Priore needed a way to turn rare books into cash. Enter John Schulman, a local antiquarian book dealer and owner of Caliban Book Shop (a well-known bookstore not far from the library). Schulman became Priore’s fence – the person who would take the stolen items and quietly sell them to collectors, often out of state or overseas, to avoid suspicion. Together, over the years, they sold off centuries-old manuscripts and prints, sometimes through auction houses in New York and elsewhere. They were careful; for a long time, nothing tied these sales overtly to the library. It was a criminal conspiracy carried out in absolute silence, right under the noses of librarians, trustees, and patrons who walked under the library’s grand rotunda never imagining such cultural looting was afoot.

The scheme unraveled in 2017 during what should have been a routine audit. The library decided to have an appraisal of its rare collections for insurance purposes, hiring an expert to inventory the Oliver Room. Red flags popped up almost immediately. The appraisers looked for one famous volume, “History of the Indian Tribes of North America”, only to find it inexplicably missing pages – likely sliced out and sold . As they dug deeper, they realized numerous priceless items were gone. The more they checked the catalog against the shelves, the more horrified they grew. It dawned on administrators that this was no small pilfering – it was an enormous, years-long theft. In the spring of 2017, library officials confronted Greg Priore. Likely realizing the jig was up, Priore confessed, implicating Schulman as well.

The revelation hit Pittsburgh’s cultural community like a bombshell. That such a revered institution had been victimized from within was almost hard to fathom. The Oliver Room’s security, once thought impenetrable, had been defeated by insider malfeasance . Rare book librarians nationwide shuddered – if it could happen here, it could happen anywhere. Law enforcement, including the FBI Art Crime Team, swooped in. Over the next year, they painstakingly traced sales and contacted buyers of rare books to recover as much of the stolen material as possible. In total, more than 320 items were found to be missing, with an estimated value of $8 million or more . Many were recovered from unsuspecting collectors who agreed to return them once told they were stolen. Some, sadly, might never be recovered – either destroyed, hidden, or too far in the black market wind.

In 2018, Priore and Schulman were indicted on numerous counts including theft and criminal conspiracy. Both eventually accepted plea deals in 2019. In a somewhat controversial outcome, neither man received a long prison sentence – Priore was sentenced to house arrest and probation (likely due to age and health), and Schulman similarly avoided prison. They also were ordered to pay restitution, though the chances of repaying $8 million are slim. Many in Pittsburgh felt the punishment didn’t match the crime, considering the cultural significance of what was stolen. But on the bright side, most of the items – some 85% – were recovered and have since been returned to the Carnegie Library’s care. The Oliver Room has been renovated with even stricter protocols, and there is now a stark awareness and caution in libraries worldwide about insider theft.

The Carnegie Library rare books heist is a tale of betrayal not unlike Konias’s, but on an intellectual level. It was a heist of knowledge, robbing present and future generations of pieces of their heritage – at least until recovery efforts made it whole again. In the annals of Pittsburgh crime, it stands out as unusual: no guns, no gangsters, no high-speed chases. Instead, a quiet, methodical theft carried out in the shadows of a temple of learning. For a local populace proud of its libraries and universities, the shock has lingered. Yet there’s also a grim acknowledgment of the cleverness involved. If the Biddle Boys or Paul Jaworski (of the Flathead Gang) were alive today, they might tip their hats at Greg Priore for pulling off a different kind of “perfect crime” for so long. In the end, this saga reinforces a hard truth: crime can wear many disguises – sometimes even a librarian’s cardigan in a hushed reading room.

Conclusion: Legends Etched in Steel City Lore

From riverfront shootouts to boardroom betrayals, these famous heists and crimes have become an indelible part of Pittsburgh’s character – cautionary tales passed down like folklore. Each era of the Steel City’s growth, it seems, cast a unique breed of criminal: the 1800s gave us desperate robbers and rebel anarchists; the early 1900s unfurled dramatic jailbreaks and trigger-happy bandits; the Prohibition years birthed mob bosses who turned city streets into battlegrounds; and modern times delivered masterminds who found new ways to steal, whether with a Glock on a bridge or a key to a rare book vault. These stories endure in local memory not just for their sensational plots, but because they reveal another side of Pittsburgh – a city of hard-working, law-abiding folks that has always had a rogue’s gallery operating in the shadows.

Yet, there’s something undeniably compelling about how Pittsburgh has responded to these crimes. For every heist, there’s a hero – be it a vigilant detective like Buck McGovern foiling the Biddles, or an intrepid librarian tracing lost books. For every gangster’s reign, there’s an eventual reckoning – sometimes delivered by the underworld itself, as with the Volpe and Bazzano saga. The city bears the scars (a bullet-riddled hat here, a broken bank vault there), but also takes a certain pride in the colorful yarns that can be spun from its past. After all, who else can claim the first-ever armored car robbery in America happened just outside their city, or that a warden’s wife once ran off in a stolen sleigh with two condemned brothers?

Pittsburgh’s famous crimes are more than morbid curiosities; they’re windows into the social fabric of their times. They highlight the tension between haves and have-nots (like Charlotte Jones in 1857, or the rank-and-file anger behind Berkman’s bullet), the immigrant hustle and occasional lawlessness in a boomtown (think of those Castle Shannon robbers in 1917 or the Monastero gang in the ’20s), and the ever-evolving dance between crooks and cops. Even as the city today enjoys a reputation as a tech and education hub far removed from its gritty past, the echoes of these old capers resonate. They remind us that behind Pittsburgh’s grit and progress lies a trove of incredible true stories, by turns tragic, ironic, and thrilling.

Walk the streets of Pittsburgh and you’ll find subtle reminders. Maybe you’ll notice the cornerstone of the old Allegheny County Jail and recall the Biddle boys’ escape, or pass by an innocuous coffee shop in the Hill District unaware it was once a notorious mob hangout. Perhaps you’ll cross the Roberto Clemente Bridge and, unbidden, think of that armored truck and the young man who gambled his soul for a shot at easy riches. These famous heists and crimes have left their mark on Pittsburgh’s geography and psyche alike. They are part of the city’s DNA – tales of steel and shadow that continue to fascinate each new generation of Pittsburghers, and will doubtless do so for years to come.

More Mobsters, Getaways, and Forgotten Crimes

These legendary heists are just the tip of the iceberg. Dive into our full Pittsburgh Mafia & Crime History collection for a deeper look at the figures and forces behind the city’s most daring crimes.

From mafia dons and outlaw duos to hidden speakeasies and back-alley deals, this hub unearths the darker side of Pittsburgh’s past—one crime at a time.

Explore the Full Crime History →